CPUSA and the Black Panther Party, An Analysis and Review of “Armed Struggle? Panthers and Communists” by Gerald Horne

By: Matthew J. Hunter

The most recent book published by Dr. Gerald Horne, “Armed Struggle? Panthers and Communists; Black Nationalists and Liberals in Southern California through the Sixties and Seventies” is perhaps his best and most applicable work to today’s communists and organizers. This isn’t the first work to highlight the history of the Black Panther Party or Communist Party USA, but this may be the first in-depth work to pinpoint that analysis to the southland of California. Why is that important? What details and conclusions in the book are worth highlighting? And most importantly, what lessons and material analysis of that revolutionary period in the mid-20th century can be drawn regarding the question of armed struggle?

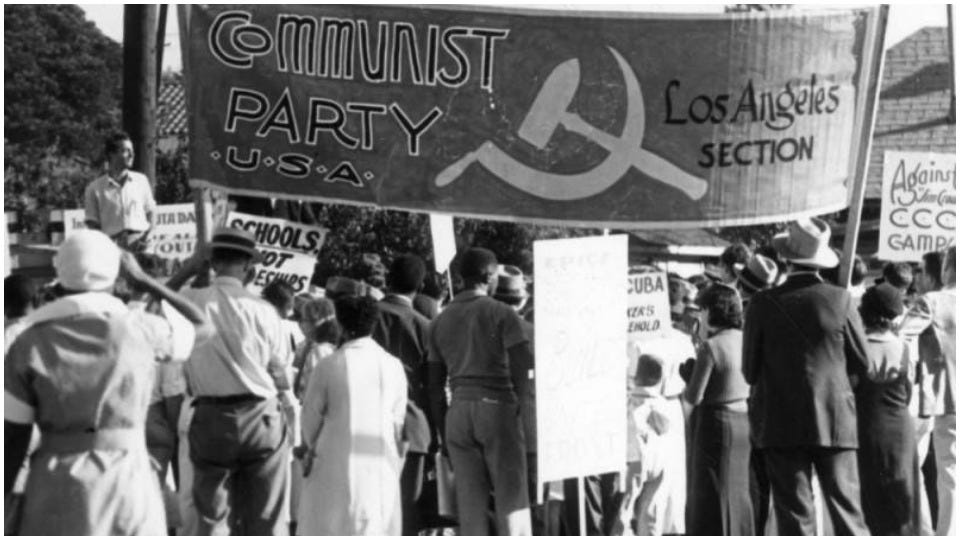

California is a land of contradictions. It is without a doubt the location for perhaps the most devastating and extreme case of Indigenous genocide and settler colonialism (read An American Genocide by Benjamin Madley). Settler colonial terrorism was a key feature of the US development of California and long into contemporary times. The level of state or state-supported violence against the Indigenous, Black, and Chicano/Latinx was extreme throughout the 19th and well into the 20th centuries. Contradictory, as Horne puts it, “…the CP [in California] was building upon a foundation of socialist ideas laid by people such as Jack London, Frank Norris, Burnette Haskell, Thorsten Veblen, Henry George, John Steinbeck—& Sinclair…As early as 1919, Oakland was viewed…as the ‘Heartland of Communism,’…” Mike Davis also in his work City of Quartz details the early socialist communes that were in the Southland in the early 20th century.

There’s a tendency, even within CPUSA historiography, to make the party activities of the West Coast lesser than the East Coast, Midwest, and even the work in the South in the first half of the 20th century. But the Party was able from an extremely early point, to build up a strong presence in California and particularly the southland. It had a sizable progressive and left-leaning base to build on. Plus the material contradictions and rapidly expanding industrial base gave fertile ground for organizing. “Why the Southland? Dialectically, the wealth generated via the studios, auto plants, rubber plants, aircraft factories, and the like led to resistance to the gross profiteering involved, from which the CP was able to catapult into prominence.”

It would become the second-highest membership per state behind only New York. Longtime California Party leader Dorothy Healy said that membership in Los Angeles County alone was over 3,000 members in the late 1940s. The proximity to Hollywood was another key part of party funding for the CPUSA and eventually the BPP through people like Dalton Trumbo, Marlon Brando, Jane Fonda, Donald Sutherland, and more.

Following the world-historical processes of the inception of US control of California–settler colonial genocide–it’s also not shocking that California was one of the first states to jump onto McCarythism, “…a Pauling biographer detected, that ‘nowhere did the anti-Communist fever rise faster or higher than in California…where as early as 1947 LA officials ordered all Communist books removed from the county libraries.’…”

It’s important to make the connection that, as Horne does, the inception of COINTELPRO in 1956 was designed and created to go after the CPUSA and eventually would tear down the BPP. The Smith Act Trial, also in the 50s, devasted the CPUSA leadership in California. Practically every leader at the state and section level was either convicted, harassed, or in some cases disappeared ominously. “The Smith Act trial proved to be devastating to the CP. Precious funds expended…mass struggle did not take a holiday, but with the comrades often missing…harm fell on their…reputation.” The judicial template for legal defense created by the likes of William Patterson, Leo Branton, John Abt, and others was crucial for the Party surviving this period. It was also a vital part of its organizing and coalition building in the proceeding decades.

The party locally made a major mistake by supporting or being indifferent towards Japanese internment. Earl Browder’s liquidationism and American exceptionalism also hurt the party’s reputation. “The CP’s calling card was that it had a scientific outlook and wholly understood the machinations of capitalism; but the Browder episode, combined with the misstep in internment, undermined its image…” CPUSA had risen to high levels of political impact through difficult mass and labor work for decades, but the Browder episode, the Smith Act Trials, and COINTELPRO devastated the Party.

An ideological pitfall of CPUSA that Horne drills home many times throughout the book is the “perceived ideological weakness of the CP in terms of being unable to detect settler colonialism in its nakedness and obviousness,” which, “created a vacuum filled by eclecticism of various sorts.” Along with the massive state-led repression of the Party, this weakness was a crucial part of the New Left's development.

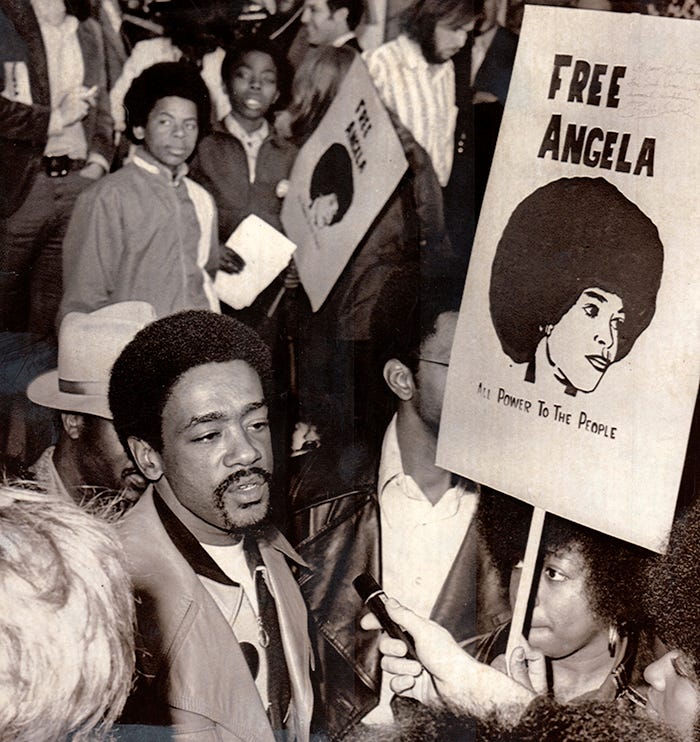

It’s almost a consensus in leftist spaces that the Black Panther Party (BPP) and the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) represent different generations of the Left and also different ideological perspectives that led to conflict between the two groups. It’s a topic that Horne does highlight. The fracture between the Old and New Left was a real fracture. What is often unknown or less talked about is the working relationship between the BPP and CPUSA. These were two organizations that, at one point, were closer to merging than taking adversarial roles. Huey Newton grew up around Party members. Angela Davis would become a key bridge between the two organizations. CPUSA historian Herbert Aptheker developed a close connection to George Jackson before his murder.

The reality was especially after CPUSA removed the right of self-determination for the Black Belt in the late 50s, the gap for organizing the Black community was wide open again. The Party had gained a giant foothold in that community through mass work for decades. Key figures like Cyril Briggs, Pettis Perry, Harry Haywood, Otto Huiswoud, Claude McKay, Franklin Alexander, Claudia Jones, and many more were also vital in this work to bridge what was at first a predominantly white and Jewish party to get a connection to the Black community. However, due to all the aforementioned reasons, a giant lane was opened for other organizations to fill that gap.

The Nation of Islam, the NAACP (after purging WEB Du Bois), Deacons for Defense, SNCC, CORE, US Organization, Community Alert Patrol, and ultimately the Black Panther Party all filled, or attempted to fill, that gap left by wounds in the Old Left–to varying ideological degrees. Malcolm X–and his assassination–along with the Watts Uprising was an epochal switch in the southland. “The Watts Revolt also marked the moment when the ideological baton in Black America was passed westward…” Only a year later, the BPP would form and it was also a local switch for Party focus. Key Black CPUSA leaders, like Cyril Briggs, Pettis Perry, Franklin Alexander, and Charlene Mitchell started the Che-Lumumba club, an all-Black club within the Party. It developed connections to the BPP, SNCC, and CORE. Along with historic Party members like William Patterson and Ben Davis, these were a real attempt to bridge the Old and New Left divide in the southland.

Angela Davis, who worked tirelessly to get famous BPP leader George Jackson out of prison, was also extremely close to the Alexander-Mitchell family. “However, this era also witnessed the ascendancy of the then UCLA professor, Angela Davis, a kind of bridge between the BPP and [CPUSA]…just as the BPP itself was a bridge between Black Nationalism and the struggle for socialism.” Jackson and Herbert Aptheker began their friendship due to these connections.

Aptheker and Jackson were perfect representations of the ideological poles their respective parties operated from. As Horne says, “The understandable tendency to homogenize the interests of the class often has led to ignoring this fundamental matter, which has contributed to seeking to compel enslaved &/or their descendants to endorse an agenda developed by the much more populous wage &/or skilled sector. This has been compounded by the inability to critique or even recognize settler colonialism, reflected in the historical summaries relied upon by radicals, such as those by Herbert Aptheker, who rarely strayed systemically beyond 1750. This truncated timeline led to taking the European presence on this soil for granted and compromised the ability to grasp firmly the Indigenous Question, along with nearly eliding the potent matter of class collaboration which inhered in settler colonialism…” Jackson’s analysis in his work Blood in My Eye squarely paints the US as a fascist genocidal regime and takes that concept to its logical conclusion in regards to organizing the masses. Yet, both men were able to become close.

When the BPP was formed, there were many instances of mutual respect by the respective leaders and their newspapers. However, when Huey Newton and Bobby Seale rather quickly were dealing with prison and court trials it left another gap. This time walked in Eldridge Cleaver. Horne spends chapters brutally detailing his abusive behavior, murderous tendencies, and ideological eclecticism. Cleaver would also end up fleeing the country to Cuba, then Algeria, France, and then eventually back to the US as a Christian conservative-Republican. He would spearhead the “Maoist” turn in the BPP that would equate the USSR with the US–alienating Cuban and other international allies–especially in Africa which received much aid from the USSR. It would be a significant issue for the BPP and the movement as armed struggle was starting.

“Armed struggle had arrived. On the one hand, this was a delayed reaction to centuries of enslavement and apartheid, backed by the state. The latter had been pursuing armed policies all along, but now the intended victims were ‘shooting back’ in organized form. A problem was the day after: Legal and mass defense that could have been aided substantially by the likes of William Patterson, who created the template in the 1930s…”

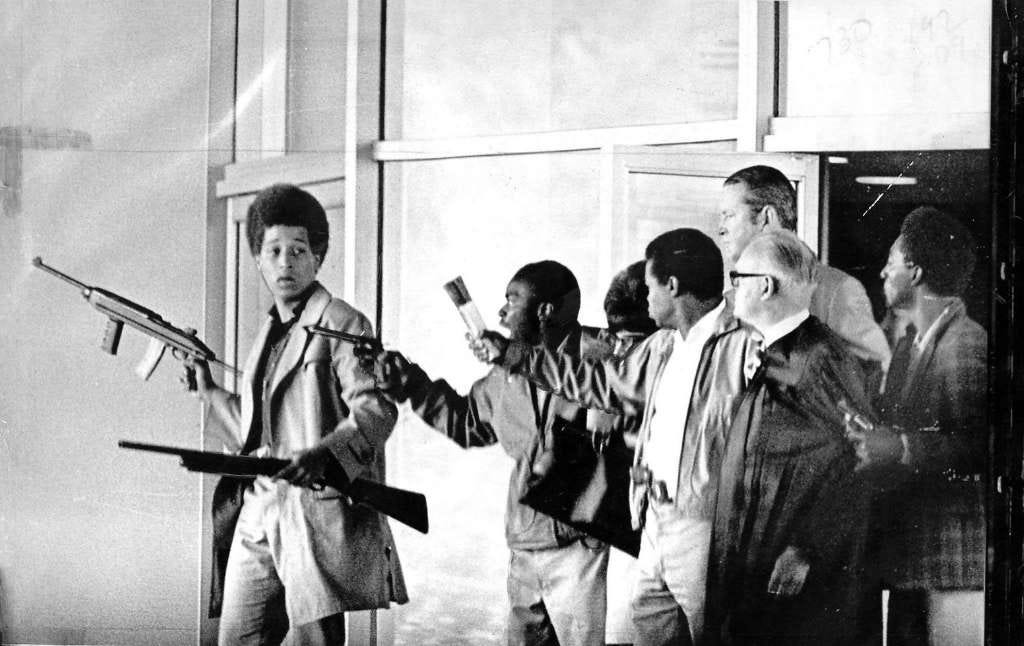

The Southland from 1965 onwards became a warzone. “August 1965 was a hinge moment in the Southland…It was epochal because of the ideological import, leading directly to the formation of the Community Alert Patrol, a precursor of the BPP, and the formation of a Black Nationalist grouping by the man then known as Ron Karenga.” The BPP was engaged in a multitude of gun battles with the authorities and Ron Karenga’s police-supported US organization. Political assassinations and disappearances were not uncommon. Dozens were known to be killed. And it ultimately led to two massive climaxes. In 1969 the newly formed LAPD SWAT laid brutal siege to the BPP headquarters in Los Angeles. The FBI and police went after the leadership of the BPP in the southland hoping to destroy it.

CPUSA members were inside the BPP HQ during the siege and were instrumental in getting local leaders in hiding or out of the country. The following year George Jackson’s brother, Jonathan P. Jackson attempted to break out other imprisoned BPP members. It led to a gunfight between authorities and multiple people, including the younger Jackson, were killed.

“Perhaps not since 1865 had there been such an organized armed resistance by young Blacks. Unavoidably, this led to something new in US politics: a movement for gun control.”

Angela Davis would be put on trial for that conspiracy. Not long before this, she had joined CPUSA and the Che-Lumumba club with Charlene Mitchell. Something she was quite open about within the trial and media–which was a sign that the Smith Act days were behind them in a certain sense. The Party used the judicial template for Davis, and even though the BPP was fractured at this point between the Newton and Cleaver factions, Bobby Seale and local BPP members co-organized the Free Angela Davis movement with the CPUSA out of the Party’s HQ in Los Angeles. This coalition and united front, which involved a massive international campaign getting millions of supporters for her freedom, was a shining example of what the CPUSA-BPP alliance could have been in the long term.

“It was also accurate to suggest the [Black Panther Party] also ‘raised the [CPUSA] into a position of great prominence in the United Front’…because of the important contributions of the CP to the legal defense of arrested Panthers despite their…Maoist literature.”

However, the Jonathan Jackson event also led to internal conflict within the CPUSA. Some such as Henry Winston and James E. Jackson viewed it as a purely adventurist event. Angela Davis, Alexander, and Mitchell pushed back against this attitude and likened the event more to a slave uprising. Eventually, Winston and others backed down in Party papers. This ideological split, also exemplified by Harry Haywood and his removal from the Party, would rear its head again in the 90s when CPUSA had a sizeable split. Davis, Alexander, and Mitchell would leave the party at that point but Horne points to this situation as the genesis for that divide.

The concept of armed struggle, the central question of the book, is not a simple yes or no question. The BPP, and other groups at the time, engaged in armed offense and defense–armed struggle. The CPUSA did not but was a central organization in the background supporting the organizations that were engaged in that struggle. But that’s not an indictment, as Horne explains, but perhaps a sign of an ideological weakness. Horne clearly shows the elements at play that are needed for armed struggle: a correct assessment of the balance of forces, international allies willing to give material aid and support, and a correct theoretical understanding of the material conditions.

The CPUSA was lacking in that latter quality per Horne, “CP comrades had the advantage of being able to consult with advanced forces globally, be they in Cuba or Southern Africa, but were handicapped by their overestimation of the fruits of 1776…the normalization of settler colonialism…an underestimation of…class collaboration…” On the contrary, the BPP was also making crucial mistakes. “Unfortunately, over time the BPP—not least because of Cleaver’s eclectic influence—was not able to strike an appropriate balance between the dual necessities of tactical non-violence and armed self-defense—and offense too, if need be.” And also their, “enthrallment with what had occurred in Cuba & what was going on in Angola, Mozambique… translating into over-determining armaments rather than a close analysis of the balance of forces in a regime…of settler colonialism and…class collaboration.” As well as the fact that those international forces in Cuba, Angola, and Mozambique were more closely aligned with the USSR. They all received huge amounts of aid and specialized training from the Soviet Bloc. Cleaver and others' vitriolic attacks against the USSR severely hurt the BPP.

The Party during this time was able to regroup. In the late 1960’s it had its first National Convention in years. Membership in Los Angeles County declined from the 40s peak but was over 1,000 members. Figures like Dorothy Healy ran quite successful electoral campaigns amassing tens of thousands of votes. However the Party, due to its ideological pitfall in regards to settler colonialism, would stagnate and decline in subsequent decades. Only as of late has the Party locally regained momentum and is close to that membership total from the 60s and 70s when Angela Davis brought a sizeable boom to the Party. The BPP was violently destroyed by COINTELPRO and the US government. Federal infiltration mortally wounded the BPP when the CPUSA was able to survive.

The inability to “strike an appropriate balance” within armed struggle by both the CPUSA and BPP led to a crisis within the Left Movement we may have still not recovered from. The BPP miscalculated or made worse the balance of forces domestically and internationally. So when they decided to “shoot back” it was from a place of alienation. The CPUSA's lack of armed defense for communities dealing with “fascist tactics” lead to alienation. Because the Party was not engaged with that it also led to stagnation, while the BPP was led to forced destruction.

Most people on the Left want to explain this phenomenon as a failure of the Old Left to recognize the US is already fascist. Horne refutes that slightly, and paints it more nuanced, “…the White House was prosecuting a relentless campaign against the [BPP] but…the nation had yet to reach fascism…What had befuddled many [including both the CPUSA and BPP] was that…the ruling class was deploying fascist tactics against Black folk and bourgeois democracy for the…settler population.” The settler colonial project, a reaction to Indigenous and African resistance in the US circumstance, is ideologically connected to fascism, the violent, reactionary, and terroristic reaction to a national crisis and a rising working class. That’s why there have been and continue to be latent fascist movements within the US.

That’s why the KKK, a fascist organization, predates the development of European fascism. The reality of this country, according to Horne, being still a bourgeois country is not to dismiss the analysis of people like George Jackson. It’s adding the analysis of settler colonialism to the question of fascism. The white settler population doesn’t face fascism. They aren’t dealing with the same America as Indigenous and Black communities and nations. And that material reality according to Horne was misunderstood by both the BPP and CPUSA.

There are many lessons and much historical information relayed by Horne in his new magnum opus. These lessons of armed struggle are even more crucial now with a resurgent Left movement and growing national crises. With the rise of overt fascist movements, with the increasing genocidal policies of the US exemplified in Palestine and against Indigenous nations, this book is a necessity for organizers. For those of us in the California southland, this book is a roadmap to where we have been and where we can go if we correctly understand how to “strike an appropriate balance” in our militant work against fascist LASD gangs and rising fascist militias in the state. It’s also a warning to how state repression, alienating theoretical frameworks, and stagnating policies can hurt communist organizations.